Megan Marz: Writing About the Internet

Poets in the Machine, Easy Answers and more.

Dear reader

I’m continuing the interviews with a conversation with the writer Megan Marz. You can find her work in Real Life, the Baffler and Washington Post, to name a few. Megan masters the internet essay, striking the magic combination of being both clever and catchy. I often refer to her in conversations about the internet.

We spoke after Longreads published her essay Poets in the Machine. It is a rare tribute to online writing in mainstream media. I wanted to know more about how the piece came together: how she collected her notes, pitched the story and worked with the editor. And I wanted to present her work to you because I’m confident you’ll cherish it too.

With care

Kristoffer

⌘

An Interview with Megan Marz

K: Do you have writings other than what’s on your website?

Megan: Yes, but in states that are not ready for public consumption. I have half-finished novel-ish projects, which I wouldn't necessarily call novels because they're so formless.

K: I like that you say it in the plural, though.

Megan: Well, it's more like starting something, abandoning it and then starting a new thing. It's not like I’m working in parallel tracks on multiple novels. It's a serial beginning and abandoning.

K: You often write about the never-ending things. Maybe it is an answer to your own writing? Instead of one book, you would write a series of unfinished novels.

Megan: Yeah, you know, I love that idea. That would be a fun concept for a project. A bunch of unfinished beginnings.

K: Why are you attracted to unfinished things?

Megan: I have always been interested in the border between everyday language and literary writing. Often writing on that border isn't locked down and finished. But it's more the intermingling with everyday life that interests me than the state of unfinishedness.

K: Not long ago, I spoke with friends about how the things we read felt like the scroll of a feed: glimpses of everyday life presented in a flow, without one master story.

Megan: It's surprising how few literary people have an aesthetic interest in how words move through computers. Life and literature mingle visibly and constantly on the internet.

K: You explain that very well in Poets in the Machine.

Megan: Thanks.

K: How did that specific piece come to be?

Megan: I initially pitched it as an article about Justin Wolfe. It fascinates me that he never turned his newsletter into a book like other talented online writers. To publish a book is the obvious way to get literary recognition, but Justin is so committed to the form of the email. I was really happy when Cheri Lucas Rowlands, the editor at Longreads, asked me: “Why don't we make it a bigger thing?” Because I had been pitching a bigger piece about online writing for years.

K: Poets in the Machine continues a conversation about literature and online writing you started with Tale Spin, published in March 2022. How do you catalogue your thoughts over such a long period?

Megan: I've tried various things. I used to retype my notes from book margins into a Word document and then categorise them. It allowed me to notice the themes but became too time-consuming to maintain next to my day job. What I do now is much more haphazard. I continue to take notes in the margin but now I just fold the corners down to indicate where something caught my interest.

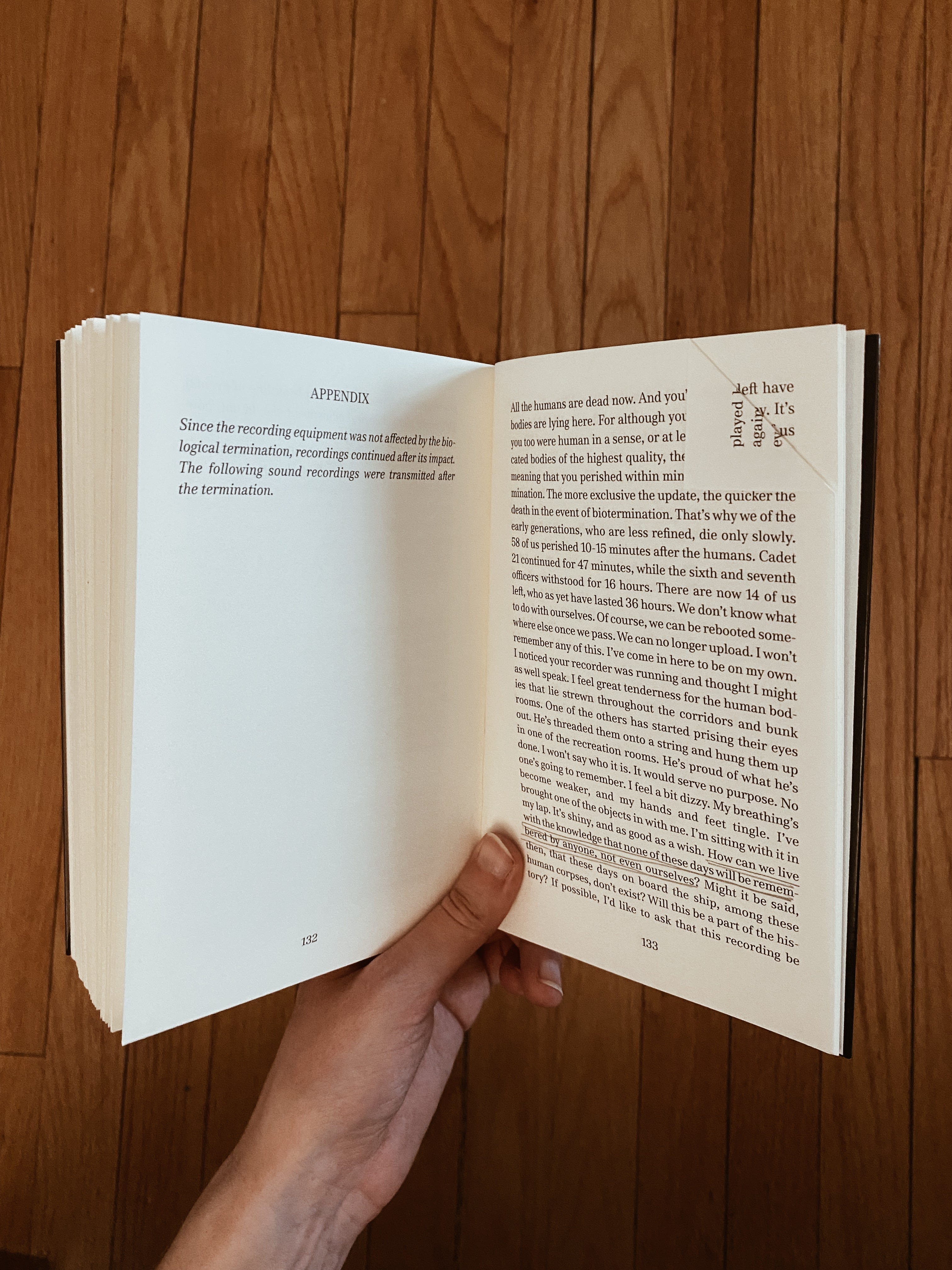

K: It sounds perfect. What works for me is a homebrewed mix of Are.na, Apple Notes and photographing book pages. I have failed at all the more complex systems I tried.

Megan: Me too. I quickly start running into the map and territory problem: At a certain point, I have so many notes that I might as well re-read the book.

K: Yeah. It is also about giving space for things to evolve and trusting that I will remember what I need to. Far from everything I was thinking about five years ago is relevant today…

Megan: Yeah, totally. When I go back to my old notes, I don’t even remember what half of them mean. But with the other half, I often realise, “Oh, this is a thought I have every week, so I don’t even need to take a note about it.”

K: I admire how Poets in the Machine relates to Tale Spin. It creates an ongoing thread about literature and online writing.

Megan: Thank you for saying that. When I read an essay collection, I enjoy tracking how the writer makes variations on the same observation, uses the same turns of phrase, or repurposes examples. Although, in some cases, it can feel repetitive.

K: But why should we not repeat things? I spend a lot of time playing with my son Uno. It involves a lot of repetition, reading the same books, answering the same questions. I think that’s good. If something is important to us, why are we not allowed to say it in many different ways?

Megan: Yeah, totally. There are a couple of pieces I like on the use of cliche that are similar to what you just said. Obviously, everyone tries to avoid cliches, but there is often power in the initial phrase and power in repetition. Cliches can be useful. It's kind of a cliche that cliches are bad; more often, they’re thoughtlessly used—which is a different problem.

K: Do you consider where you publish your writing? Does your writing change depending on the venue?

Megan: It is mainly the editing process that changes the writing. For example, Real Life had a very rigorous editing process. I worked with two editors, Rob Horning for the first essay and then Alexandra Molotkow for the rest. They were both particularly smart about structure and also about cutting stuff that was boring and superfluous. It was great to have someone telling me: “get these paragraphs out of here.” I miss Real Life a lot.

K: I miss Real Life too. But I would also be curious to read the cut-offs from the pieces you wrote for them. Real Life was incredible at critical essays about the internet, but I also see auto-fictional strength in your writing. It appears in glimpses, for example, in Seen By, where you write about the male person who harassed you.

Megan: I love personal writing, too. I’ve mostly worked it into other kinds of essays because that feels less scary than writing something straightforwardly personal.

K: Your personal writing would be a valuable addition to internet writing which tends to be either boosterism or criticism.

Megan: This reminds me of a book I reviewed by the scholar Mark McGurl. He has a line about how everything written about the Internet has this correctness that is no match for overfamiliarity. Personal writing can be a way to get around the overfamiliar “correctness” of internet criticism.

K: How about the reading experience? Do you consider where people will read your work? Whether your writing is published behind a paywall?

Megan: It's less about the UX of the website and more about what other writers the site is publishing and its politics, commitments and ethos. Is it a larger project that I'm excited about contributing to?

There is a lot of opacity around what and how people are reading. I’d be interested to learn more about that in a non-creepy-surveillance-y way. A long time ago, I was in charge of an email newsletter for a job at a hospital and had to report on the open rates and click-through rates. When I logged in to see the numbers, it was almost impossible not to see data on the level of the individual. The newsletter was for the doctors. It felt weird to see the names of the doctors who would open or not open the newsletter. On the other hand, I don't know if any of this means what it's supposed to. They may have opened it, but how often do you open something only to delete it?

K: In Tale Spin, you mention that you used to type URLs directly into the Internet Explorer address bar. Do you still remember any URLs by heart?

Megan: It was basically just blogs I was reading, like emilymagazine.com, bitchesgottaeat.blogspot.com and Orangette, the cooking blog by Molly Wizenberg. I think that was orangette.blogspot.com. There was another blog that was sort of like a dating diary called something with “cocks and dolls.” I don't remember the exact URL. I think it still exists, but it's been dormant for a long time. It was an anonymous one. And then there was Kate Zambreno’s francesfarmerismysister.blogspot.com. I think some material from there went into her book, Heroines. And then Bhanu Kapil's blog, jackkerouacispunjabi.blogspot.com.

K: Did you start a blog yourself?

Megan: No.

K: Not even an anonymous one?

Megan: No. Part of my attraction to people writing online is that I'm dispositionally disinclined to do it. I write very, very slowly. I am also shy. Many people say they are shy in real life but can express themselves easily online. I’ve never felt that way. I feel just as inhibited about personal blogging and social media. So I appreciate how much skill and talent it takes to be good and successful at that kind of writing, because I would be bad at it.

K: Besides the blogs, are there any domain names you remember? Maybe some more recent ones?

Megan: Most of the websites I visit are small magazine websites. I would go to Real Life when it was active, reallifemag.com. Now I go to the Baffler to see what's on. I’m actually not sure if it is baffler.com or thebaffler.com? I think it's thebaffler.com, but I don’t know for sure since it appears when I start typing it in the navigation bar. I don't actually have to remember the URLs anymore, only enough to start typing them.

K: I think search engines did to domain names what the mobile did to phone numbers. I remember phone numbers from my childhood, but none from recent years. To take back a sense of control, I’m trying to remember URLs by heart, like meganmarz.com.

Megan: That’s very sweet. A few years ago I reviewed a book, Fragments of an Infinite Memory, that argues search engines flipped the dynamic between personal and factual memory. The argument is that, before the internet, it was easier to access our own past experiences than, for example, the dates of historical events. But now that we can so easily retrieve basic facts, our personal histories are less accessible by comparison. The author describes the strange frustration of not being able to google what he did the night before.

Most days I don’t mind if I forget what I did last night because I can’t look it up, or forget a URL because I can look it up so easily. As you said earlier, at some point you have to trust that you’ll remember what you need to. And I’d rather save the brain space for, like, lines of poetry. Though of course a URL can also be a line of poetry.

You can find links to more of Megan’s work on https://meganmarz.com. I regret I didn’t find a way to include Easy Answers, her essay about the answers we get from search engines.